- Why Nagoya Is a Paradise for Fermentation Lovers

- What Makes Nagoya’s Flavors So Distinct?

- Essential Nagoya Foods and How Fermentation Shapes Them

- Kakukyu

- Kobanten Hanare Itto

- Lunch at Kobanten Hanare Itto

- Hitsumabushi and the Art of Layered Flavor

- Curry Udon: Not Traditional, But Telling

- Kishimen and Regional Soy Sauce

- Yamashin

Why Nagoya Is a Paradise for Fermentation Lovers

Nagoya is sometimes described as a city people pass through rather than stop in, despite it being Japan’s 4th largest city. But for travelers interested in food, that reputation quickly becomes hard to understand. This is one of Japan’s most important regions for fermented foods, and its culinary identity is deeply shaped by centuries of brewing, aging, and microbial craftsmanship.

Aichi Prefecture produces many of the fermented staples that underpin Japanese cuisine: miso, soy sauce (including tamari and white soy sauce), vinegar, sake, mirin, and pickles. These are not niche specialties, but foundational ingredients that quietly define Japanese cooking at every level. What makes Aichi special is not just the volume or variety of fermentation, but how visibly alive the culture still feels. Many production sites are not preserved relics—they are working spaces, worn by time and use, where fermentation continues much as it has for generations.

For travelers, this means Nagoya offers something rare: the chance to taste history not as a concept, but as an everyday practice.

What Makes Nagoya’s Flavors So Distinct?

At the heart of Nagoya’s cuisine is umami, the deep savoriness produced through fermentation. This flavor comes from the work of microorganisms, especially koji mold, which transforms starches and proteins into sugars and amino acids. Koji underpins miso, soy sauce, sake, mirin, vinegar, and even many pickles, making it one of the quiet heroes of Japanese food culture.

Aichi’s climate helped fermentation flourish. Warm, humid summers, fertile soil, and easy access to water, salt, rice, soybeans, and wheat created ideal conditions for brewing. During the Edo period, the region also benefited from stability, strong rice harvests, and proximity to Edo (modern Tokyo), allowing large quantities of sake, vinegar, and mirin to be shipped east. Over time, producers learned to repurpose by-products: sake lees became vinegar, miso runoff became tamari soy sauce, and mirin lees were used for pickling. This all became a symbiotic fermentation ecosystem where almost nothing was wasted.

The result is a flavor profile often described as bold, rich, and unapologetically deep. Compared to the lighter seasoning styles of other regions, Nagoya cuisine embraces intensity, but always with balance and purpose.

Essential Nagoya Foods and How Fermentation Shapes Them

Miso-Based Dishes: Depth Over Delicacy

While Japanese food tends to highlight simplicity and minimalism with flavor, miso can actually be contrasting depending on the dish. If you are a fan of bold flavor and things like dips and sauces, it’s probably worth searching for dishes that depend on miso!

Nagoya’s most famous ingredient is soybean miso, often aged for two years or more. Long fermentation produces a dark color, earthy aroma, and powerful umami. This style of miso was historically favored by a powerful samurai leader, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who unified Japan and founded the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan’s military government, in 1603 and its influence still defines the region’s cooking.

At places like Kakukyu Hatcho Miso Traditional Brewery in Okazaki, visitors can see this process firsthand: enormous wooden vats bound with bamboo rings, weighed down by carefully stacked stones, quietly fermenting for years. The miso made here becomes the backbone of classic dishes such as miso-katsu and miso-nikomi udon.

Eating miso dishes after seeing how they are made changes the experience entirely. At the Okazaki Kakukyu Hatcho Village Restaurant attached to the Kakukyu Hatcho Miso Traditional Brewery, meals are not just flavored with miso, they are contextualized by it. Staff and guides explain the aging process casually, sometimes with humor, making a centuries-old craft feel approachable rather than academic.

In Nagoya city, Hekinan city, and surrounding areas, restaurants like Hanare Ittō located in Hekinan city show how these traditional flavors are carried forward. The cooking is refined, but the foundations remain unmistakably local: miso, soy sauce, and fermented seasonings used with restraint and confidence.

Kakukyu

With an official founding in 1645, Kakukyu is the definitive name in Hatcho Miso production. As one of the largest producers of traditionally made Hatcho Miso, they have elevated their historical prowess into a luxury ranking, offering premium miso. Their unique production strategy involves aging their miso for at least 2 years in massive cedar vats and using a traditional stacking method of over three tons of river stones to press the miso. Kakukyu is a leader in both production technique and heritage protection, even going so far as to purchase new wooden vats to support manufacturers, despite the existing vats lasting for over 100 years and improving with age.

The massive property has long withstood the test of time, an impressive sight that highlights the devout maintenance of their production methods. Each person encountered seemed enthusiastic and proud of the operation. It is clear that their stance on production has remained as stable and unwavering as the stones they stack.

Address: 〒444-0925 Aichi, Okazaki, Hatcho-cho 69

Kobanten Hanare Itto

Led by executive chef and owner, Hayahisa Osada, this establishment is a fine way to enjoy a selection of the local food. After graduating from university, he trained at a traditional Japanese restaurant in Tokyo, ultimately choosing to revitalize his hometown of Hekinan City through cooking.. He is committed to a farm-to-table philosophy, meticulously sourcing ingredients from within the local area to create food that is deeply authentic to the region. Dishes featured soy sauce from Nakasada Shoten and Yamashin, sake from Sawada Shuzo, and miso from Kakukyu, a reaffirmation of these facilities’ firm positions as Aichi’s pride in fermented foods. His dedication extends beyond the kitchen, as he actively supports the community by connecting local producers and even offering college lessons to aspiring individuals.

The restaurant itself presents a stylish and traditionally Japanese aesthetic, offering a refreshing, upper-class atmosphere well-suited for both lunch and dinner. During a visit, the chef’s genuine excitement to share his creations was evident; he was consistently smiling, happy to engage, and eager to answer any questions about the dishes. The staff mirrored his demeanor, proving to be just as friendly and attentive, ensuring the entire dining experience is thoroughly enjoyable for all guests.

Address: 〒447-0874 Aichi, Hekinan, Sakuzukamachi, 1 Chome−16

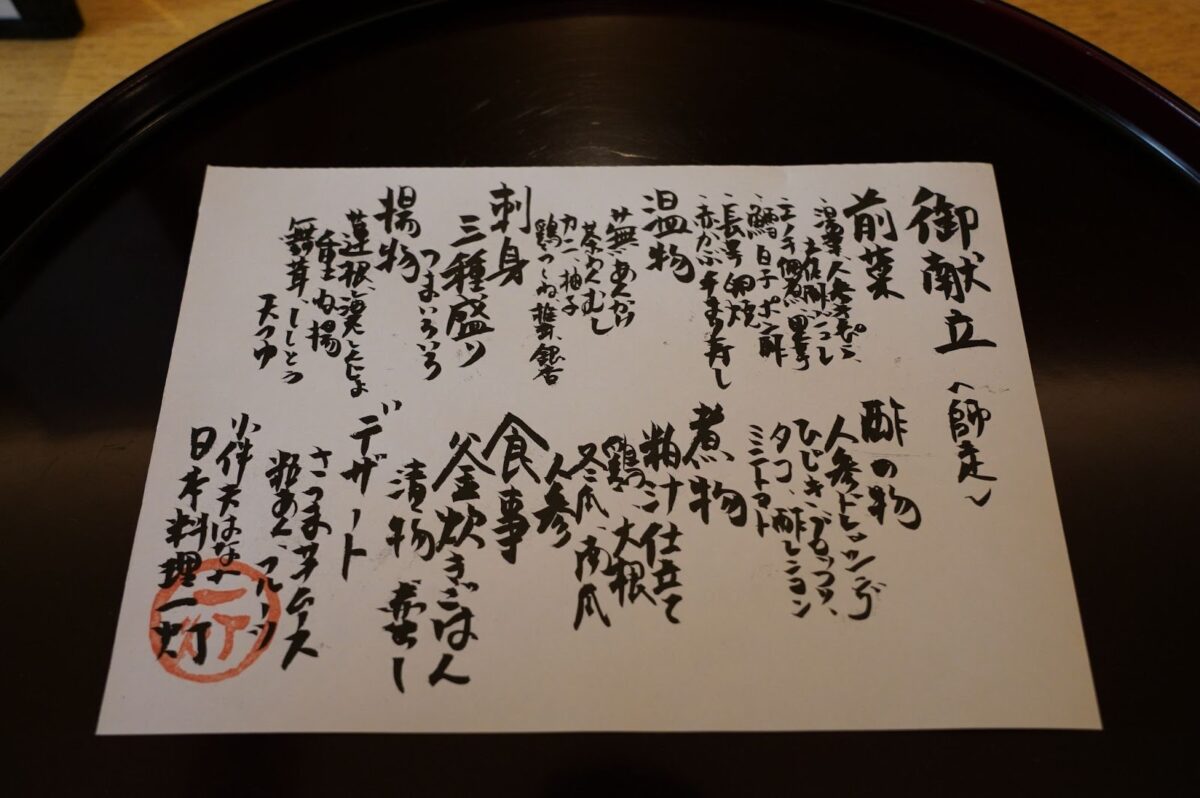

Lunch at Kobanten Hanare Itto

Hand-written explanation of the course meal

Chawanmushi (Savory Steamed Egg Custard):

Crab, yuzu citrus, chicken meatball, ginkgo nuts, and shiitake mushroom

Assorted sashimi served with locally made soy sauce

Assorted Tempura of Lotus Root and Maitake Mushroom served with locally made tempura sauce

Kasu-jiru (Traditional Soup Made with locally made Sake Lees)

Featuring chicken, daikon radish, winter melon, kabocha squash, and carrot

Takikomi gohan (rice mixed with vegetables and whitebait) with Nakasada Shoten/kakukyu miso soup

Sake from Sawada Shuzo “Hakurou”

Hitsumabushi and the Art of Layered Flavor

Hitsumabushi, Nagoya’s signature grilled eel dish, relies heavily on fermented seasonings for its complexity. The tare sauce used to glaze the eel draws depth from soy sauce and mirin, ingredients whose character develops only through time and microbial action.

This layering mirrors Aichi’s fermentation culture itself: flavors built gradually, not rushed, and designed to unfold as you eat.

Curry Udon: Not Traditional, But Telling

Curry udon is not historically considered “Nagoya-meshi,” yet it appears frequently on local menus. Its popularity reflects how deeply fermentation has shaped regional tastes. Even when borrowing from nontraditional dishes, Nagoya cooks often lean into rich dashi, miso influence, and fermented depth, making the dish feel unmistakably local.

Kishimen and Regional Soy Sauce

Kishimen, Nagoya’s flat noodles, are typically served in a soy-based broth that highlights regional variations in shoyu. Aichi is home not only to tamari soy sauce, thick and intensely umami, but also to white soy sauce (shiro shoyu), which is lighter in color, wheat-forward, subtly sweet, and incredibly versatile.

Producers such as Yamashin Soy Sauce Brewery help illustrate how diverse soy sauce can be. White soy sauce, in particular, is often described as versatile and modern, appealing to chefs experimenting with lighter presentations or fusion cooking, while still grounded in traditional fermentation. If you like cooking, they offer a wide array of products that will really allow you to see that versatility.

Yamashin

The legacy of Yamashin, founded in 1802, is currently shepherded by Shinichi Okajima, the 8th generation leader. Mr. Okajima is credited with elevating Yamashin’s famous shiro shoyu (white soy sauce), which is uniquely characterized by its high ratio of wheat to soybeans (usually 50/50, while Yamashin uses 90% wheat), from a regional condiment to a luxury-market ingredient, positioned for use in international cuisines like French and Italian. Its unique ability to enhance umami without imparting dark coloration is recognized. Mr. Okajima was recalled as a man of great warmth and vitality. An admirable rapport with his team was evidenced, and value is clearly seen in opening doors to tourism as a means to strengthen brand recognition and showcase artisanal quality. He is impressed upon as an astute businessman who balances running a modern enterprise with fiercely protecting historical roots. This philosophy is perfectly mirrored in the facility itself, where a beautiful balance is struck between traditional reverence and pragmatic innovation. A respect for history is embodied in the operation, producing a product true to its origins yet thoughtfully optimized for a modern ecosystem. This measured approach ensures that a beloved, high-quality product can reach more people, more efficiently, while its excellence is maintained.

Address: 〒447-0064 Aichi, Hekinan, Nishiyama3-36

Experiencing Fermentation Beyond the Plate

A scale model depicting vinegar production and shipping during the Edo period, on display at the Mizkan Museum that showcases the brewing culture of Handa, which has developed alongside the local community through mechanical devices (brewery, water facilities, and canal formation).

One of Aichi’s strengths as a food destination is how accessible its fermentation culture is. Many sites welcome visitors not just to observe, but to engage.

At larger institutions like Mizkan Museum, visitors learn how vinegar played a key role in Edo-period food culture, including the rise of nigiri sushi, and sushi as it is known now. The experience is polished and informative, helping visitors grasp the historical importance of fermentation on a national scale.

Yasunori Nakagawa explaining wooden vats and the production method of tamari soy sauce at Nakasada Shoten

Smaller producers often leave a different impression. At places like Nakasada Shop or Sawada Sake Brewery, the atmosphere is more intimate. Conversations are casual, explanations are often accompanied by charming humor, and tasting directly from vats or tanks creates powerful sensory memories. Smell, in particular, becomes a teacher: the sweetness of mirin in the air, the sharpness of fermenting soy sauce, the deep earthiness of miso rooms. These moments tend to linger long after facts fade.

Sawada Shuzo is dedicated to upholding specific, time-honored production methods, which are the secret to their sake’s renowned, exceptional quality:

Pristine Water Source: The essential brewing water is sourced from a natural spring, channeled two kilometers from a nearby hill directly to the brewery using privately maintained pipes.

Harnessing Nature’s Chill (Ibuki-oroshi): During the colder months, the brewery ingeniously utilizes the Ibuki-oroshi, a cold wind sweeping in from Mt. Ibuki, north of Aichi Prefecture, to achieve efficient natural cooling. This is why the buildings are specifically oriented to face northwest, the direction of the wind’s arrival.

Traditional Rice Steaming: Steaming the rice is a process that foregoes modern machinery in favor of the koshiki, a traditional wooden steamer. This classic tool is key to ensuring perfect, even heat retention and precise moisture control.

The Art of Koji Cultivation: The crucial koji cultivation process is executed using koji-buta: small, individual wooden trays. This meticulous approach guarantees the koji mold adheres uniformly to every single grain, ensuring the rice’s inherent umami dissolves completely to enrich the final sake.

Kaoru Sawada explaining the role of koji-making in sake brewing at Sawada Shuzo

At Kokonoe Mirin, visitors learn how mirin, made from glutinous rice, rice koji, and shochu, comes together to create this unique ingredient. Comparisons to simple syrup help demystify its role, while displays of World Expo award certificates hint at its historical global reach.

A staff member explaining kai-ire (the stirring process) Kokonoe Mirin

For those wanting broader context, the Brewing Tradition Museum in Taketoyo Town ties these threads together, explaining how miso, soy sauce, sake, and vinegar industries grew interdependently, sharing materials, techniques, and even philosophies.

Mizkan

Founded in 1804, Mizkan stands as an ecological innovator whose impact profoundly established trade routes with Edo. The company’s rise coincided with the surge in popularity of edomae sushi, for which vinegar was an essential component. This burgeoning demand for vinegar necessitated increased trade and, consequently, the ships to facilitate it. The fundamental genius of Mizkan was a revolutionary and foundational act of taking “waste,” specifically sake lees, and transforming it into vinegar. This unique production method not only supplied ingredients but also allowed Mizkan to effectively engineer eating habits.

The company’s philosophy heavily celebrates innovation, always drawing inspiration from its deep roots. Mizkan successfully occupies a space that is both traditional and modern, understanding that being forward-moving is its heritage and perpetually valuing its past successes.

A visit to the museum offers a profound experience, unequivocally illustrating to the visitor the monumental nature of the innovation and implementation of something seemingly simple, like vinegar. It serves as an excellent example of the meticulousness inherent in Japanese production, as well as the deep value placed on heritage. The visit is certain to inspire visitors to seek out dishes crafted with vinegar.

Address:〒475-0873 Aichi, Handa, Nakamura 2-6

Nakasada Shoten

The current CEO, Yasunori Nakagawa, represents the sixth generation to lead the company, which is famous for its high-quality tamari soy sauce and miso, and has a history stretching back to 1879. One of the defining features of Nakasada Shoten’s production is the traditional kumikake method. Rather than adding new ingredients, this technique involves drawing soy sauce that has collected at the bottom of a wooden vat and ladling it through a pipe back over the top layer of soybean mash. By repeatedly circulating the liquid in this way, the rich umami of the inner layers is slowly extracted, deepening flavor over time.

He joined in 1999 and was appointed Representative Partner in 2003, having become part of the family through mukoyoshi (son-in-law adoption). His wife, the rightful heir, also plays an active role in running the shop. Mr. Nakagawa is a kind, softly spoken, and highly intelligent leader. He approaches the business with a compelling blend of scientific rigor and genuine enthusiasm, and he possesses deep knowledge about every step of the process.

He has a gentle sense of humor, too, cracking a witty joke about a support beam in the facility that had been shifted by an earthquake, (and how he’s waiting for it to shift back with the next!). Don’t worry, it’s totally safe. The facility itself is a testament to the company’s long history. It appears that changes have only been made out of absolute necessity; this preservation contributes to the product’s perceived purity, deeply rooted in its origins.

Address:〒470-2343 Aichi, Chita, Taketoyo, Komukae 51

Sawada Shuzo

Founded in 1848, Sawada Shuzo, a renowned brewery famous for its sake, is currently led by the exceptionally confident and knowledgeable 6th-generation head, Kaoru Sawada. Her eloquence and approachable demeanor are matched by her deep commitment to quality, a dedication she likens to caring for her own children: each type of sake a unique creation that requires love and care. She claims to be unable to drink that much alcohol, but can definitely evaluate the quality. While her husband, Executive Vice President Hidetoshi Sawada, works directly on the brewing floor, Kaoru guides the facility’s operations. The brewery itself masterfully incorporates its long history into its present-day operations, where the evident dedication to quality, instinctive flexibility, and operational efficiency ensure that every historic structure and tool serves a clear, modern purpose. This dedication includes unique production methods, such as their special way of mixing in koji mold into the rice by hand repeatedly in different patterns.

Address: 〒479-0818 Aichi, Tokoname, Koba 4-10

Kokonoe

Founded in 1772, Kokonoe holds a distinguished place as one of the oldest mirin breweries in Japan where Mikawa mirin was born, making it one of the established authorities on its production. The secret to their unique flavor lies in the very structure of their 1706-built warehouse, which was astonishingly relocated in 1787. The resident microbes within the aged wood impart a unique aroma, essential to their Mirin product’s distinctive taste. This traditional method relies on natural saccharification and ripening, the process of converting starch into sugar, which sweetens the mirin without the need for any added sugar. This incredible combination of history and quality has made Kokonoe an essential brand among discerning chefs.

A walk through the historic warehouse is an impressive experience, particularly when the massive quantities of cooked glutinous rice are being poured out. The resulting aroma is profound; intensely palpable and pleasant, yet never overwhelming. It’s a scent that immediately sparks hunger and a sense of calmness. The staff, from the brewers to the guides, appear genuinely excited and enthusiastic to be part of an establishment so long-standing and prestigious.

Address:〒447-0845 Aichi, Hekinan, Hamaderamachi 2-11

Craft, People, and the Feeling of Something Alive

What many visitors notice is that fermentation in Aichi does not feel staged. Floors are worn. Buildings lean slightly. Wooden vats darken with age. Time is visible everywhere.

Knowledge here often appears embodied rather than written. Brewers adjust movements instinctively. Every role and every step of the process is treated as crucial. In fact, the stones that are stacked on top of the mix of ingredients that become miso are stacked with incredible precision: this role takes about 10 years to master, with those masters claiming that each stone has a “face” which allows them to know exactly where to place it. These stories are abundant and often paired with a lighthearted attitude; you’ll be lucky to meet the people involved.

Leadership also feels personal. Brewers describe products as living things. Family successors speak less about legacy and more about responsibility. Even practical decisions, like purchasing extra wooden vats to protect the deep heritage of the vat-making craft as the industry shifts to cheaper products, reflect a broader sense of care over control.

Practical Travel Planning for Food Lovers

Nagoya is easy to reach from Tokyo and Osaka by Shinkansen, and international travelers arrive via Chubu Centrair International Airport (NGO). For those exploring fermentation sites around the Chita Peninsula or planning early departures, the Four Points by Sheraton Nagoya Chubu International Airport offers a supremely convenient and comfortable base.

The hotel is located very close to the airport terminal with a covered walkway in a part, making it an ideal choice for travelers. It takes about six minutes to walk from the airport’s train station, which offers rapid access to central Nagoya (Meitetsu-Nagoya Station) in less than an hour (at least 30 minutes) via the Meitetsu μ-SKY Limited Express. This direct connection makes it an excellent launchpad for exploring the wider region.

This hotel provides upper-level comfort with essential amenities to ensure a pleasant stay. Guests can enjoy complimentary high-speed Wi-Fi throughout the property and a modern 24-hour fitness center. It is also an excellent choice because it combines modern comfort with exquisitely prepared food that incorporates the flavors of Aichi into delicious dishes. The way that fermented foods can enhance dishes with umami and other notes is incredible. If you want to see just how impressive it can be, be sure to order their specialty items at the on-site restaurant, Evolution. Entrees, side dishes, drinks, and desserts all have Aichi’s outstanding array of flavor incorporated beautifully.

Most fermentation destinations are accessible by train, bus, and short taxi rides, making it feasible to explore without a car, using the hotel’s excellent connectivity as your starting point.

Dinner at Four Points by Sheraton Nagoya Chubu International Airport

Carpaccio of Kumano Sea Bream with ginger & Toyota soy sauce dressing (Kinshibori tamari)

Carbonara with Moriguchi radish & anchovy/capers (Moriguchi narazuke)

Crab omelette with wasabi mayo, white miso & mustard broth (Toyota Masuzuka raw koji miso)

Salt-koji marinated Chita beef fillet with hatcho miso & hishio miso (Mikasagi Kojiya salt-koji)

“The Chita” whiskey cocktail

Locally brewed Miso-infused Beer

Nigorizake (unfiltered sake) cocktail

Sake lees tiramisu (Shiraoi aged sake lees)

Sample Fermentation-Focused Routes

These sample routes offer a structured way to experience Aichi’s fermentation culture, combining food, history, and production sites. Each itinerary is designed to be achievable within a day while highlighting the diversity of fermented foods unique to the region.

One-Day Fermentation Route: Departing from Nagoya City

Morning | 8:30 AM – 11:00 AM | Local Fermented Cuisine

- Focus: Begin the day with classic Nagoya dishes that showcase Aichi’s fermentation heritage.

- Dining/Activity: Find a local restaurant specializing in misokatsu (pork cutlet with thick, dark, umami-rich soybean miso sauce) or kishimen noodles (flat, wide wheat noodles often served in a miso-based broth).

- Interesting Points/What to Do: These everyday meals provide an accessible introduction to the bold, umami-forward flavors created by Hatchō Miso, a local variety of soybean miso aged for years. Look for restaurants near Nagoya Station or the Ōsu Shopping Street for traditional preparation.

Afternoon | 1:00 PM – 4:00 PM | Mizkan Museum (Handa)

- Focus: Explore the history of vinegar production and its role in shaping Japanese food culture.

- Activity: Visit the Mizkan Museum in Handa (about a 30-minute train ride from Nagoya). The museum requires advance online booking.

- Interesting Points/What to Do: Exhibits connect Aichi’s brewing traditions to the rise of Edo-period cuisine, including sushi, as Mizkan was the first to successfully mass-produce vinegar made from sake lees suitable for sushi rice. The museum features interactive displays, a look at the historical brewing tools, and often offers a small tasting of different vinegar based drinks.

Evening | 7:00 PM onwards | Dinner at Hanare Ittō in Hekinan city

- Focus: Conclude the day with dinner where traditional techniques and fermented seasonings are incorporated into refined Japanese cuisine.

- Dining/Activity: Experience a multi-course kaiseki or set menu at Hanare Ittō (or a similar high-end restaurant focused on local ingredients).

- Interesting Points/What to Do: The chef utilizes local fermented products like shio kōji (salt fermented rice), various regional soy sauces, and, of course, miso, often in surprising and modern ways. The meal reinforces how historical fermentation methods continue to influence modern, elevated dining, providing a sophisticated contrast to the morning’s hearty dishes. Reservations are highly recommended.

One-Day Fermentation Route: Okazaki & Surroundings

Morning | 9:00 AM – 11:30 AM | Kokonoe Mirin (Hekinan City)

- Focus: Explore the history and traditional production of Mikawa Mirin.

- Dining/Activity: Visit the historic Kokonoe brewery, known for its long-fermented, high-quality mirin.

- Interesting Points/What to Do: Touring the facility introduces visitors to the traditional slow-brewing method, including the use of steamed glutinous rice, rice koji, and shochu, which creates the deep umami and sweetness of Kokonoe Mirin.

Lunch | 12:30 PM – 1:30 PM | Okazaki Kakukyu Hatcho Village Restaurant

- Focus: Experience dishes centered on locally produced Hatcho miso.

- Dining/Activity: Enjoy a meal at the on-site restaurant.

- Interesting Points/What to Do: Dining here helps connect production methods directly to flavor and everyday use in traditional cuisine.

Afternoon | 2:30 PM – 4:30 PM | Kakukyu Hatcho Miso Traditional BreweryVillage Craft (Okazaki City)

- Focus: Explore the history and production of Hatchō Miso.

- Dining/Activity: Visit Kakukyu, one of Aichi’s most iconic soybean miso producers.

Interesting Points/What to Do: Touring the miso storehouses introduces visitors to long-term fermentation, stone-weighted vats, and the deep flavors that define Hatcho miso.

One-Day Fermentation Route: Chita Peninsula

Morning | 9:30 AM – 11:30 AM | Brewing Tradition Museum (Taketoyo Town)

- Focus: Gain an overview of the Chita Peninsula’s fermentation history.

- Dining/Activity: Visit the Brewing Tradition Museum.

- Interesting Points/What to Do: Provides useful context before visiting active producers, covering sake, soy sauce, and miso.

Lunch/Early Afternoon | 12:30 PM – 2:30 PM | Yamashin Soy Sauce Brewery or Sawada Sake Brewery (sake)

- Focus: Choose between two distinct koji-based fermentation experiences.

- Dining/Activity: Visit Yamashin Soy Sauce Brewery or Sawada Sake Brewery

- Interesting Points/What to Do: Observe hands-on techniques that contrast with larger heritage producers, emphasizing craftsmanship and direct engagement.

Evening | 7:00 PM onwards | Local Dining Influenced by Traditional Techniques

- Focus: End the route with a meal featuring local fermented seasonings.

- Dining/Activity: Dinner at a local restaurant rooted in the Chita Peninsula’s brewing traditions.

- Interesting Points/What to Do: The meal reinforces how these traditional techniques remain a vital part of everyday regional cuisine. Reservations may be recommended depending on the restaurant.

Taste the Living History of Nagoya

Nagoya rewards travelers who slow down and pay attention. Here, fermentation is not a trend or a performance. It is a quiet, ongoing conversation between time, microbes, and people. By tasting, smelling, and meeting those who guide these processes, visitors come away with more than good meals. They gain a felt understanding of why flavor, place, and history are inseparable in Aichi.

For readers interested in the deeper historical and cultural forces that shaped this food culture, Article 1 provides that background. Together, the two stories offer a complete picture: not just of what to eat in Nagoya, but why it tastes the way it does.